This is the third session in the Turning Lessons into Legacy learning series on learning in programs, as organisations and in an equitable way, together with partners. In the first session, we examined how program-specific lessons can be turned in and used as organisational legacy for future programmes. During the second session, we looked into what organisational conditions are needed to make the best use of their staff, ensuring that learning enhances impact. This final session, Partos, together with academics, researchers and partitioners looked into equitable strategies for learning with partners.

An academic perspective on equitable learning

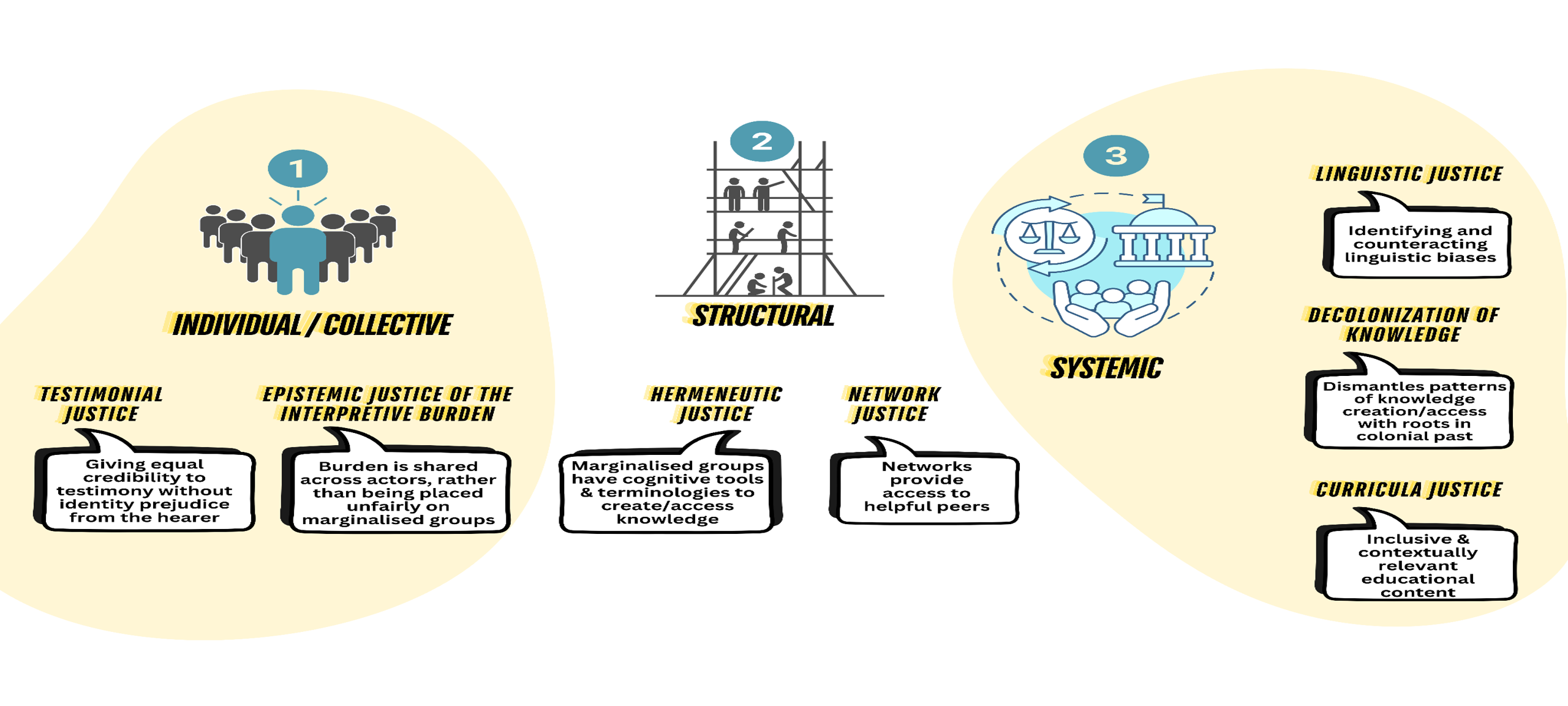

Gladys Kemboi, who works for the University of Illinois, and is knowledge café leader in the Knowledge Management for Development (KM4Dev) Community of Practice started off the session by outlining what inequalities still exist in the knowledge system, and how we can address them. Local knowledge and Indigenous knowledge holders are often excluded from multiple knowledge systems. This ties to the concept of epistemic, or knowledge related, justice. In their paper, Gladys Kemboi, together with her co-authors[1] frame epistemic injustice as “unfair treatment in which the voices, experiences and solutions of marginalized individuals, communities and societies are ignored.”

To help signpost the way towards epistemic justice, the authors developed a framework outlining what we can do and what systems need to be in place in order to fairly and justly treat all stakeholders in learning processes. Doing this is important, not only because of the moral imperative, but also because “listening and valuing the knowledge of all stakeholders will lead to better knowledge and more effective change processes.” For a complete overview of the framework, please read their article.

Finally, Gladys Kemboi presented the activities of the Knowledge Management for Development (KM4Dev) community, whose members work on the decolonisation of knowledge and learning, and discuss ‘uncomfortable truths’ through for example knowledge cafes. If would like to connect with other knowledge professionals and learn how you can put equitable learning strategies into practice, check out the Knowledge Management for Development (KM4Dev) website. This global community of practice shares theory, practice and related matters in their events, such as the upcoming knowledge café on July 8th, 2025!

[1] Sarah Cummings, Charles Dhewa, Stacey Young and Mike Powell.

Putting research into practice

Building on the academic foundation of equitable learning, ALNAP researchers Hana Abul Husn and Mae Albiento shared key findings from their paper, Advancing Locally Led Evaluations: Practical Insights for Humanitarian Contexts. They highlighted the role evaluations can pay in promoting equitable power relationships within partnerships. Given the significant investment of money, time, and energy in evaluations—and their influence on decision-making—evaluators inherently hold power and responsibility in shaping outcomes.

Next to this awareness of evaluators’ power, it’s also important to consider whether your MEAL strategy promotes equitable learning within your partnerships. Does it facilitate equitable dialogue around design, participation and decision making?. Does it account for power dynamics? Reflecting on these questions can help in ensuring your learning strategy promotes an equitable partnership.

So, what practical steps can organizations take during evaluation design? Albiento offered several suggestions. In the planning stage of an evaluation, particularly during the development of the Terms of Reference, organisations can require team members who are knowledgeable in the language and cultural practices of the communities involved. Another example is to allocate funding for engaging with communities during data collection as well as in the reporting and use phases of the evaluation. This enables communities to help interpret findings and contribute to shaping recommendations, ultimately helping them reflect on how to sustain initiatives themselves.

For more practical recommendations on advancing locally led evaluations, we encourage you to explore the full ALNAP research paper.

A practical perspective on equitable learning

Finally, Sarah Okello and Nyakato Bitamisi shared practical insights into feminist learning approaches at Akina Mama wa Afrika, a pan-African feminist organisation that envisions a dignified and equitable feminist society.

Historically, they followed a linear learning process. This process was planned alongside the strategic plan and guided by a learning agenda. They noticed it helped provide clarity and structure, and made it easier to track progress. However, it also had some shortcomings. It’s inflexible, resource heavy, limits innovation, real time adaptation, and being able to use diverse sources of knowledge.

Realising this, AMwA noticed that that this linear approach failed them. They had low responses to their surveys, evaluations and feedback forms. Gains fluctuated across different variables. With feedback from partners, consultants and others they worked with, AMwA decided to change their approach. They started this process by fostering a culture of open, non-defensive listening and revisiting its own history. They redefined learning as a shared responsibility, prioritizing internal knowledge systems and centering the voices and experiences of staff, partners, and alumni. This was supported through the creation of both internal and external learning spaces, enabling ongoing dialogue and collective growth.

This new approach is called emergent learning. It arises from practice, and is shaped by the context, partners, & the fluidity of AMwA’s social justice work. It is an iterative, innovative and reflexive approach that embraces uncertainty and feminist curiosity. This approach is more flexible, it honours multiple ways of knowing, and adapts in real time. However, a drawback is that it demands comfort with ambiguity & shared power. Currently, AMwA uses both linear and emergent learning, using the different strengths of both strategies.

Closing words

In the discussion with the participants, it was noted that learning is often inhibited by strict donor requirements. The speakers shared the importance of having conversations with funders to understand each other’s point of view and try to find room for flexibility and compromise. At the same time it is important to think about the power you do have and explore where in the learning of evaluation process you can make some (small) changes to make practices more equitable.

Throughout the session, a few reflections stood out. At the core of strong partnerships is the simple but powerful act of seeing each other as human beings. Learning happens best when we feel safe—not just physically, but also emotionally and mentally. That means creating space where people feel heard and respected. Whether we are local partners advocating for leadership or allies at the table, we must ask ourselves: are we truly listening? Are we recognizing the wisdom of those closest to the context?

To move toward more equitable learning in partnerships, we must be willing to reflect deeply, challenge entrenched systems, and decolonise MEAL practices. This involves courage to try new approaches, to elevate them as viable models, and to take small but intentional steps within our own spheres of influence. It’s through these actions that we build trust, shift power, and cultivate learning that is truly collaborative and just.