It is important that everyone gets a chance to speak up about their own challenges. Therefore, I believe that we need more changemakers around the world who amplify these voices and it doesn’t matter what method they use.

During the Partos Innovation Festival, Mohammed’s unique mission to tell untold stories and impactful method to create change stood out and inspired the room. As part of the Inclusive Communication Community of Practice, we want to dive deeper into his motivation, mission, and method to showcase his truly inclusive approach to other actors in the social change field. Are you looking for ways to improve your communication practices and mobilize people to create social change? Mohammed Hammie’s stories are leading the way.

What is your story? What has inspired you to become a changemaker?

As a journalist, I’ve seen that people living in rural areas are not given a platform in mainstream media to raise their voice. I quit my job in 2019 as a radio editor to change this and become a bridge between communities and political leaders. I decided to focus on water, because I believe it’s the solution to many problems related to health, education, and poverty. It can even bring peace to communities.

I am passionate about doing journalism differently to help communities, but a good changemaker needs to have a tool. I first chose to work with community radios, which are very popular in regions not yet reached by social media. I established my radio program Sauti Yangu-means ‘My Voice’ in Swahili: a 30-minute unique and powerful show that aims to engage citizens, amplify their voices, and pressure the government to resolve the water crisis in rural areas.

However, I felt I could do more. Why not collect grassroots stories from these communities and write a book so that their voices can reach every corner of the globe? My father was a great author in Tanzania, so it’s in my blood to write stories. But I didn’t want to write popular novels, such as detectives. I wanted to tell the untold stories, so people learn from each other’s experiences and change their lives.

All the cases I wrote in Mandiga’s book are real. They are based on my visits of different villages and extensive engagement with the communities I write about. When I go to the villages, I don’t carry food or water. I eat there and drink their water. That’s my mission, to amplify their voices and save lives.

What is the impact you aim for by writing Mandiga’s Well? What kind of world do you want to create with your stories?

This book is educational and inspirational, reminding us that change starts with one person’s courage to pursue a better future. As we say in Swahili: mandiga alianzisha mwendo na alifanikiwa kupaza sauti na kijiji chake kupata maji.

Mandiga—the protagonist of this story—is a woman, because in many African community’s women are responsible for fetching water and they face many challenges. Therefore, I wanted to empower and increase the confidence of women to find solutions. However, if you read my book, you will realize that it’s not only about water issues. I use this challenge as a way to show other hidden values that are not spoken of. I raise the issue of violence against partners, the responsibility of leaders to be transparent and accountable, and the importance of overcoming shame and fear to speak up about developmental challenges.

I believe there are many Mandiga’s in the community and all they need is encouragement to create change. With this book I hope to provide them with a role model. In Tanzania we say, if you empower a woman, you empower society.

Read an extract from the book: Mandiga Chapters6&7

How have you been able to reach your goals so far? Can you give an example?

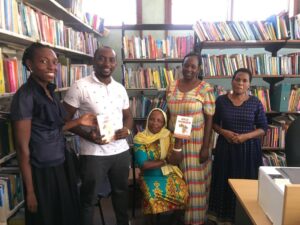

One of my goals was to distribute Mandiga’s book for free to increase its outreach and impact. First, I managed to print five hundred copies by saving my own money and I distrusted it to rural areas and regional libraries for students to read.

After many people read the book, the demand became greater than I expected. People liked the quality of the story and the way it reflected the realities of the community members’ daily lives. The news of Mandiga’s Well spread to the colleges and universities. It’s now, for example, being studied, at the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM) and it will be read in secondary schools across Tanzania with support of the Ministry of Education.

Mandiga’s Well is not just a book, but a tool to change the community and enable people to amplify their voices. When they see themselves in the stories they read, they will be inspired. Not only as changemakers, but also as upcoming authors who aim to write impactful stories.

However, there are many places in Tanzania that I have not yet reached. Using different types of media can help improve our outreach. In collaboration with Simavi, Mandiga’s Well has been converted into a comic. Now, I wish to make a film or radio play as well to broaden the story’s impact.

Have you encountered any difficulties? Can you give an example?

Originally, I wrote the book in Swahili and based the story in the village of Kikwawila. The residents are from the Wandamba tribe, one of the ethnic groups in the Morogoro region. I stayed in that village for one month to understand their lives and behaviors. In the book, I translated some words into the Ndamba language to bring the realities in that area to life. For example, waba… waba… wabambo wala wang’wila, wang’wisha pasi, wang’onjeka, meaning that they knocked me over and raped me. The words that Ashaneza said when she was called to the village meeting and explained the rape while she was going out to fetch water.

The most difficult part was translating the book into English. I wanted it to be done by a fellow author who knew Kiswahili and English well. Although it didn’t take me long to find that person, the challenge was the translation costs. The publication was delayed, because I had to work hard to get the money. I am determined to distribute the book for free so that its message can spread to the greater African community and other parts of the world, especially English-speaking countries. Because stories like Mandiga’s are not only Tanzanian, but people from other countries can also relate. I received many comments from readers from Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, Ghana, and Nigeria, who say that the issues I wrote about in the book are similar to what is happening in their countries, especially in rural areas.

Therefore, I would like to take this opportunity to emphasize to the international community the importance of funding locally owned stories. Supporting us in printing more copies and distributing to rural areas will greatly benefit these communities.

According to you, what are the key ingredients of a good story? How can stories mobilize others to do good?

First of all, it’s about being a skilled writer so that the reader doesn’t put the book down. There are many issues to write about in society and if the writer does that skillfully, the book can be good and go far. For example, a storyteller must have a straight flow and expand it as the story introduces new characters. Mandiga’s book started with a woman who survived rape, then her husband came in to the picture, later on she went to the village government to report the crime, followed by the village meeting, and finally the whole community listened to her message.

Secondly, a good story touches the real lives of the community members. For example, in Tanzania, if the author writes about water challenges, he or she will touch a large group of people. Also, issues of poverty and hunger, the challenge of access work for young people who graduate from college, mother and child health, menstrual hygiene and gender issues, and poor education are important to people. By giving real examples, I build trust and encourage others that they are not alone in the challenges they face. These stories have an emotional appeal and can mobilize others to do good.

Finally, writers should know very well what message they want to convey to the readers and when. It is better to choose a message that targets a large group. If you look at the cover of Mandiga, you will see that I have used a map of Africa. Mandiga is carrying a jerry can while on the map, because I aimed for the book’s message to reach the whole of Africa: a character who is experiencing challenges and finding a way out. It makes it easier for people to imitate those behaviors and continue the bravery they read in the book. I give them hope and make them feel that it is possible to succeed.

What has been a key lesson in your own journey as a changemaker that you would like to pass on to others?

In a globalized world, it’s hard to believe that there are people whose voices are not recognized. It is important that everyone gets a chance to speak up about their own challenges. Therefore, I believe that we need more changemakers around the world who amplify these voices and it doesn’t matter what method they use. It can be writing news, making films, making radio plays or programs. Towards 2030, the end of the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, it is important everyone gets a chance to be heard and we don’t leave anyone behind.

CoP Inclusive Communication

The next Inclusive Communication Community of Practice session on the 24th of January will go deeper into the content creation process of social change actors and its opportunities and challenges. Partos is bringing together a diversity of changemakers from the international development sector to reflect on old, current, and new narratives in the field. Together, these changemakers are creating a common language that is ethically sound, morally justifiable, and creates a positive impact for the people we aim to support.

Asma Naimi PhD

Assistant Professor, Writer, and Social Entrepreneur

This column is based on the upcoming Storytelling for Social Change Guidebook, a collaboration between Changemaker Studio and Shortway Productions. The guidebook shows how storytelling is essential to create awareness about societal challenges and to make an impact by combining insights from ancient methods, groundbreaking artists and the latest science on social movements.